My first job with the Thiel Foundation was organizing an event called Breakthrough Philanthropy. Breakthrough Philanthropy was meant to showcase Peter’s support of transformative technologies and brilliant minds. It was supposed to seed the idea in the minds of current and up-and-coming benefactors that there was more than one way to impact the future.

Giving to hospitals and orchestras is a deeply worthy pursuit, but hospitals and orchestras aren’t where the future is shaped. They’re more like the gilded caboose on the Orient Express — useful, beautiful and purposeful, but lagging far behind the future speeding ahead. For us to stay relevant, we need new engines. For us to leap ahead, we need airplanes. That’s what Breakthrough Philanthropy was about.

The event showcased Peter’s donations to Foresight Institute, XPrize, The Seasteading Institute, and others. We sent a clear message that day, but it is now apparent to me that it wasn’t bold enough. I am unclear on whether we inspired enough people to engage in the kind of breakthrough philanthropic giving we need for a bolder and better future.

I hosted this event a few months before the whirlwind of the fellowship took the global stage by storm. Some of you may remember the reception we received back then. Larry Summers called the Thiel Fellowship “the most misdirected piece of philanthropy” in history. A few turned us into the favorite target of their columns over the years. The first few years were intense.

I think it’s safe to say that we proved them all wrong. We didn’t just give gifted young people the chance to throw metaphorical grenades at college — we touched on something very important; giving money to people, not institutions.

It is such a simple idea, but it is astonishingly hard to do. In the US, if you give anyone over $16K, you are required to report it to the IRS and can be taxed on that money. When the fellowship launched, the world saw Peter on stage at TCD shaking up the foundations of the academic world, but what they didn’t see was the squad of high-priced lawyers and the formidable Jonathan Cain ironing out the details.

As a non-profit, you can’t just give people money. No matter how much sense it makes. You have to first talk to people in bespoke, very well-tailored suits. Is it any wonder that the great art of patronage has been reduced to seemingly eccentric philanthropists and their small circle of benefactors?

In popular culture, acts of patronage, mutual aid, and almonry are treated with the same regard as someone announcing that they’re taking a winter break with their local axe murderer. What insanity! From childhood, we in the US learn that giving to our family members is a terrible idea that turns loved ones into bratty strangers. Forget actual strangers! After all, what does a stranger have? Some ideas? A few materials? Maybe some small recognition from an institution? At most, a recommendation from a friend.

In our culture, this is tantamount to building a bridge with wet tissue. No matter the circumstances, we’ve been indoctrinated into believing that giving money to people is a Really Bad Idea™.

But is it?

Going back to my early days with the Thiel Foundation, I’ve always wanted to do a very particular photo shoot ever since the very beginning. It’s based on the iconic PayPal Mafia image, but with something more historic in mind.

The main foldout would include Peter, the foundation board of directors, and foundation staff all sporting Renaissance garb – high collars, frilled cuffs, dark rich colors, and broad shouldered silhouettes amongst the Boboli Gardens. Individual pages would highlight the young people and academically dismissed scientists that the foundation supported that would later go on to be seen as transformative technologies and businesses like Ethereum, the Longevity Fund, Luminar, Figma, and OYO rooms.

The image would have been a bridge from the past to the future and from the future to the past; a continuation of a great tradition under a very different form. When Galileo Galilei sat down to contemplate the cosmos, he did so with the assistance of Cosimo de Medici. When Austin Russell sat down to contemplate lasers, he did so with the assistance of Peter Thiel.

The Thiel Fellowship was a challenge to two big norms: that college was the only right path for young people and that making a real and recognized contribution was something you did once you did what everyone else told you to do: go to school, get a job, and get experience.

Our program was radical for going against the grain. We encouraged teens 19 and younger to apply for our program where they would be given free reign over their futures to work on a project of their choosing for two years, with $100K, and the support of our program. Our program asked a very dangerous question: why not?

Why not allow for a different future than the one that had come before? Why not dream big about what young people are capable of doing?

In answering our question, we ended up building a structure that works for high agency people that enables them to harness the better angels of their nature and bring forth their vision into the world with a little support along the way. This statement isn’t a contradiction in terms; being high agency is synergistic with the right supportive environment. The whole becomes more than the sum of its parts.

Looking back, it was a time where the existing “fellowships” targeted people in the middle of their career. People who were already established and doing work within a narrow set of parameters. What made the Thiel Fellowship work wasn’t just whom we targeted, i.e. high agency young people for whom “some ideas just [couldn’t] wait,” but also how we supported them.

The fellowship part of the Thiel Fellowship was extremely important. It was a cozy, well-knit environment that supported the agency and actions of these individuals. It’s a model that doesn’t work well “at scale,” but where it does work; it works. And this model is at the heart of this essay.

I believe that if we let a thousand such programs bloom, we will plant the seeds of a new renaissance. A heterogeneous chorus of voices building and giving rise to new science, technology, and art.

Many readers will recoil at the above words; “Danielle, if these programs are so great, then why aren’t more people doing them?” The answer to that question goes back to whom we vest our trust in and how.

From the youngest of ages, we’re taught to trust a higher authority, an unassailable institution more than other people. This phenomenon is new. You don’t have to look too far back find a time where people lived in tightly knit communities where they trusted one another more than large, impersonal institutions. In Europe, this changed sometime before the dawn of the industrial age, in concurrence with the rise of urbanization, absolutism, corporations and mercantilism. As we moved away from the hamlets and into the cities, there was a sustained, conscious effort to shift the focus of our trust from individuals to institutions.

It is not surprising that this shift occurred, but it is deeply disappointing. We dehumanized the interactions that mean the most. Once unrooted of the bonds between us, we became dependent on entities that are simultaneously afflicted with human vices while being beyond human chains of accountability.

With the launch of ChatGPT, my social media timeline has been filled with AI doomers preaching a technoapocalypse. But their apocalypse has already come to pass. We already live in a world governed by inhuman beings without any kindness or empathy. We call them by many different names, but they share the same DNA; manifested towards the same end. With apologies to Charlie Stross, we live in their world, on their terms, subject to their whims and valued accordingly. Be it the paper belt or a faceless corpo, the result is the same.

These large institutions have warped our world. We now fervently believe that these soulless entities are inherently more trustable than our fellow humans. Institutions have logos, buildings, name brand donors, and sometimes, historical significance with astonishing hydra-like attrition tolerance— all to prove that they are grand and safe. Safe for you and your money. Individuals have none of that. They are paupers next to the grandeur of old banks with their marble pillars, safes, and starched shirts.

In this world, throwing your weight behind these institutions is the logical choice. Some will argue that it is the correct choice. But it is not the only choice. It takes eccentricity to recognize that. It takes dollops more to go against the grain and make a different choice. And that’s what a fellowship — at its very best — is. A highly personalized and individualized program that makes a different, suboptimal choice.

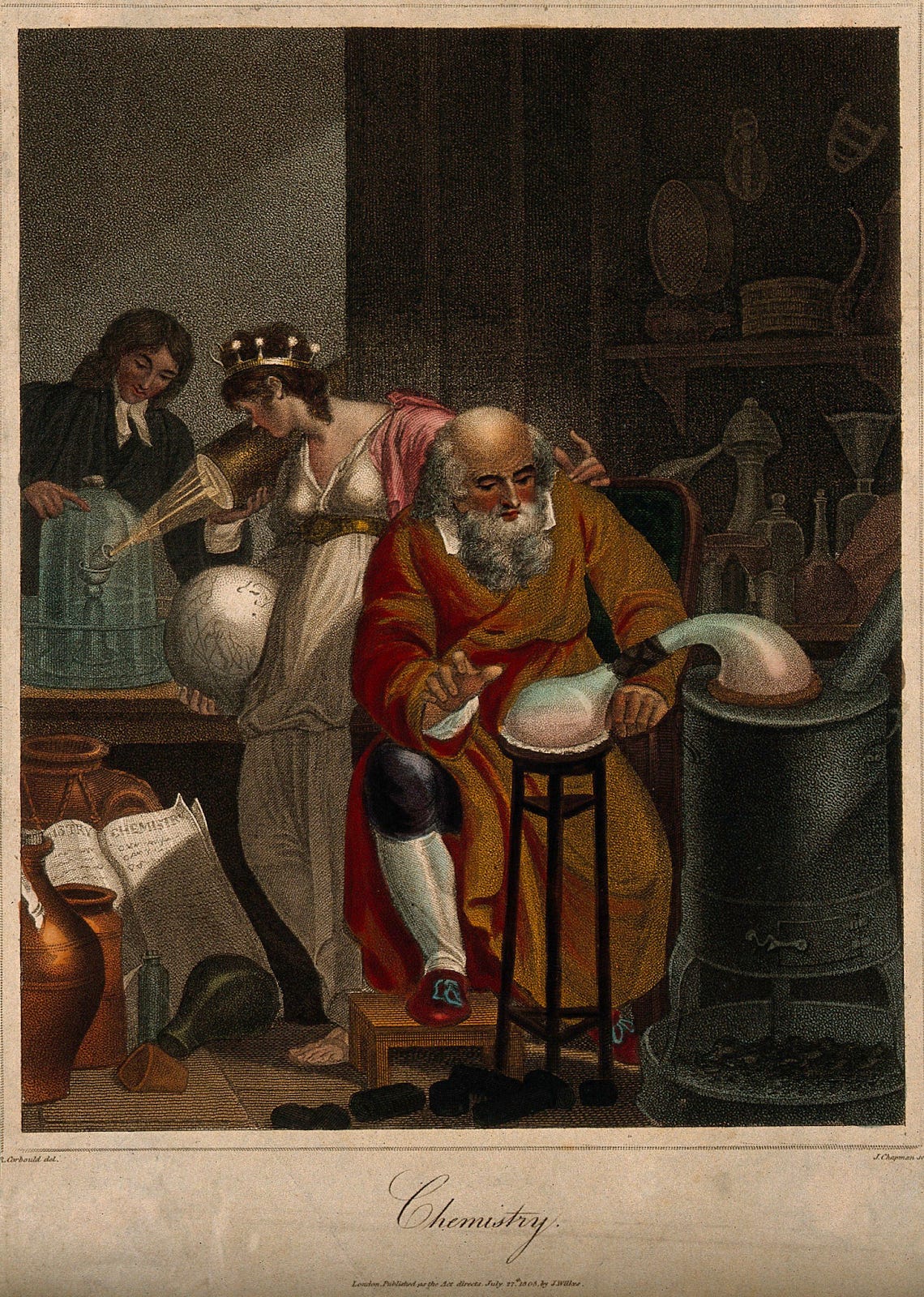

Making this suboptimal choice is nothing new. We stand in the shoes of giants. There is a long standing tradition of moving the world forward with what some might see as a flagrant misuse of capital. Throwing capital as if it is meant to do no more than show off one’s refined tastes and appetites — it was called patronage.

Patronage is as old as money itself, if not older. However, we have come to associate it with Florence’s the House of Medici for good reason. After all, they funded the geniuses who begat our modern world; Leonardo, Galileo, Michelangelo, Fra Angelico and even Machiavelli. Every child is on a last-name basis with these figures, we’re taught of their greatness, but we’re rarely taught about how effective the system that produced them was.

The Medici were a strange family, egalitarian in some ways, authoritarian in others. They were the eccentrics of their time, the weirdos who believed in their philosophy of supporting great works so much that they took it with them no matter where they went.

Married off to a French prince at the age of 14, Catherine de' Medici, came to power through a twist of fate and then used that power to do what her family had always done; seed the future. She invested heavily in the arts, architecture, haute cuisine1, theatre, and the performing arts. Her investments led to the creation of the most French of art forms, the Ballet,

The person who made ballet a fashion trend [..] was the Italian art-lover Catherine de Medici. When she married the French King Henry II, she [..] contributed to the development of the ballet by providing the necessary financial support. In fact, Ballet Comique de la Reine, [..] was organized under the order of Medici, [making] history as the first ballet show.2

Today's historians write that her massive investments bore no lasting fruit, and her patronage had no impact. And yet, despite the best efforts of her political opponents, it is remarkable that so much of what we consider quintessentially French was derived through her largesse; through her willingness to make the eccentric choice. They tore down her buildings and smashed her paintings, but they still couldn’t erase the fruits of her largesse.

Today, this great art of directly supporting great artists, scientists, and individuals is largely carried out by two groups: eccentric philanthropists and ordinary people.3 But no matter who does it, they usually fall into two camps; those who directly support individuals and those who focus on specific themes and projects.

The first group is the most fascinating to me; the ones who directly sponsor artists to create and produce — sometimes offering space to live or show one’s work and make connections with interesting minds who might offer further support and inspiration. You never know what could influence a budding career or shape a new artistic direction.

Such direct support might be the best way to bring together brilliant minds and watch the sparks fly. It is exhilarating and breathtaking to witness greatness take shape.

There is no perfect strategy here — a "best way" — to bring such people together, save for giving them resources and the space to create. In my line of work (venture capital), everyone acts like there is a specific recipe that can be implemented to bake the perfect startup cake — engineer, hustler, usually from such and such institutions. But that's almost never true. Just because someone comes from Harvard and looks like Mark Zuckerberg doesn't mean that they will be Mark Zuckerberg. Greatness exists in just too many forms and flavors.

Scholars have typically defined creativity in two broad domains;

Big-C creativity — Meitner and Frisch's discovery of fission; Huygens' pendulum clock; Mayer's shell model and magic numbers; Maxwell's color photography, equations, and control theory

Little-C creativity — This essay and its thesis, 1517's Twitter feed, and the art you made as a child (and hopefully still do)

Typically, programs claim to aim for the Big-C variety, but they often fall somewhere in between, depending on their outlook and risk appetite.

In my experience, people falter because they refuse to accept that Big-C creativity can come from the most unexpected of sources; especially if they’re young.

In the 1960s & 70s, a housewife with no formal education beyond high school, started fervently following Martin Gardner's Mathematical Games column. In 1975, Martin Gardner wrote a column repeating a mainstream mathematician's claim that they had found all of the possible convex polygons that could be tessellated to fill a plane.

Within a month, a reader (Richard James III) wrote in with a new polygon tiler. Rice saw this success and started working on the problem "on [her] kitchen table when no one was around and hiding them when her husband and children came home, or when friends stopped by." By February 1976, she'd discovered a new pentagon type and developed custom notation. By October, 58 pentagon tilings that could transitively tile a plane. Before the end of 1977, she'd discovered four pentagon tilings and 103 transitive tilings.

No one would have pegged Marjorie Rice as a mathematical genius who would revolutionize the esoteric geometric subfield of Euclidean plane tilings by convex regular polygons. Or, would continue to be of assistance to the field for the rest of her life. And yet she did. The startup equivalent of this would be someone like Vitalik Buterin, a no-name 20-something with a white paper who goes against mainstream consensus to create the next great leap ahead. Most dismissed Buterin at the start. They don’t do so anymore.

It’s rare that we encounter someone — like Stephen Balaban, founder of Lambda Labs — who represents the opposite case. Someone you just know is going to make a large impact — one way or another. But no matter how obvious it is at the start, both of these groups share a few deep commonalities. They both go off the beaten track and end up having singular needs that must be fulfilled for them to realize their potential. Both groups are also small and finite, which makes them hard to cultivate. What makes it even harder is that both groups are subject to the whims of the power law in action. To me, it makes sense that a fellowship can’t serve two masters. Finding, cultivating and unleashing the Marjorie Rice’s of the world is very different from doing so for a ferociously fast prodigy. Their needs are just too divergent.

I’ve spent most of my life around young people with divergent needs. First, as a teacher and school principal at Innovations Academy, then as a part of the Fellowship and now at 1517. I’ve come to believe that the more exceptional the person, the more unique their needs.

As a society, I think we confuse their unusual needs for a lack of needs. The needs of some of the young people I’ve worked with through the Fellowship and 1517 aren’t conventional, but they are just as present and real. If they are to grow to make full use of their intellectual capabilities, their appetite and hunger for knowledge, resources, mentors, peers, and (yes) capital needs to be met. Just as some people need extra French tutoring. Others need scanning electron microscopes.

This fact brings us back to something that we’ve already touched on above — i.e. the fellowship cannot scale. This is true. But neither can our current educational system.

A bold shift is required if we are to move away from this broken cycle to something better for future generations.

I have a simple proposal; we shouldn’t pretend that one size fits all, that a single program or model can serve the entire world. Instead, we should seed as many small programs and models as we possibly can. Let a thousand flowers bloom and stand back to see what takes root.

I want everyone, including you, to experiment with what a fellowship should and could be. If there's no guaranteed way to find and support greatness, then we should explore every single possible way to do so. Every community, philanthropist, and thinking person should take the plunge and explore how they want to empower the extraordinary in their daily lives. The more eccentric your approach, the better.

One example I would like to highlight is the Seven Seven Six Foundation. Alexis Ohanian launched their fellowship program when he noted that “nothing matters if planet Earth is fucked.” His solution is to empower creative people who are on the margins and can take the risks needed to arrive at a breakthrough. Their model is a radical departure from conventional thinking. The foundation doesn’t even ask for college degrees or credentials! (“because it doesn’t matter.”) They’re laser-focused on their vision of the world and how they believe they’ll find the people who’ll fix what matters.

Seven Seven Six isn’t alone. In my opinion, fellowships like the Thiel Fellowship, O’Shaughnessy, Magnificent Grants, and more are doing some of the best work out there to support individuals through direct support. Their takes are different, but they share the same mission; to empower amazing people to do awesome things.

I believe in this so much that I (and 1517) are trying to bring together incredible people who are starting such programs around the world so that they can share what they’ve learned along the way and grow together. I would like you to join us in this mission so that we can, together, create another renaissance.

I want us to light the world on fire by unleashing our creativity and energy in the most unexpected of ways. I want us to free the weird and the marginal so that we can all shape a better future.

This past April, I and 1517 had the good fortune of organizing a summit for fellowship leaders to share learnings, ideas, and communities. It was a blast (should you like to join in the future, email me)! We called it Renaissance Reimagined because we truly believe these communities are the key to birth of a new era. An era guided by people with strong sensibilities, like the Medici, who come forward and directly support people that they think are special and then let time do the rest.

It is time for us to let go of our obsession with credentials and enjoy, envision, and inspire each other together. If this strikes a chord and you run a fellowship program, please reach out! We want to see a thousand fellowships bloom!

With love,

Danielle with awesome historic nerdy from Anna (areoform).

via Wikipedia, “Diderot and d'Alembert's Encyclopédie published in 1754, [..] describes haute cuisine as decadent and effeminate and explains that fussy sauces and fancy fricassees arrived in France via ‘that crowd of corrupt Italians who served at the court of Catherine de' Medici.’”

If only they knew.

Ayvazoğlu, Seda, and Kerem Özcan. "From court to theater in the 18th century: birth of the ballet d’action (dramatic ballet)." Journal for the Interdisciplinary Art and Education 2.1 (2021): 1-8.

"Don't forget to like, subscribe and support me on patreon"