Inside v. Outside Context Problems.

Or, why smart people are bad at making predictions about the future.

a personal observation & hypothesis

This post is the result of two personal observations:

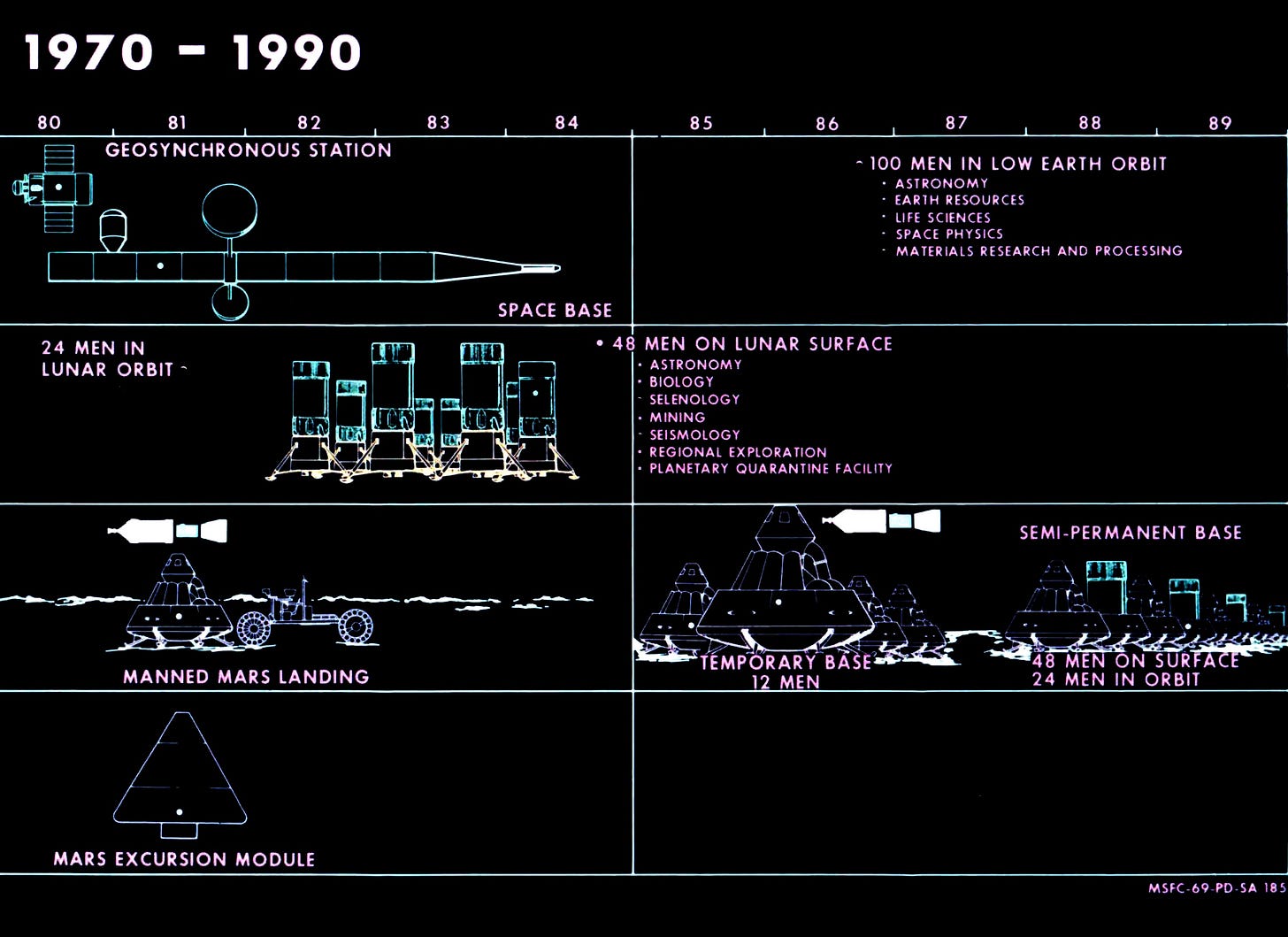

Observation 1: Smart people extrapolate outwards from themselves and their social environment. In predicting technological trends, they are unable to accurately gauge broader political, social, and economic forces that shape technology. Example, predicting outwards from the phenomenon that was Apollo, smart people in the 60s believed that we would be on Mars by the ‘90s and 2000s. Or, more recently, the laments that followed Segway and Google Glass.

Observation 2: The magnitude of the error increases depending on whether they can imagine a direct use-case or not. If a technology/product can be viewed as “just a toy,” or a recombination of older, more established technologies, then its impact is more likely to be dismissed.

It is my personal hypothesis that some experts discount the ability of ‘mundane’ technology to change the world. Or, more generally, when making predictions, experts are biased towards overestimating the impact of seemingly new and radical technologies while underestimating the ones we view as mundane.

For example, Kurzweil’s predictions from The Age of Spiritual Machines are often fantastic and full of sci-fi tech like,

"Phone" calls routinely include high-resolution three-dimensional images projected through the direct-eye displays and auditory lenses.

He predicted direct retinal projection via lasers and holographic gratings, but he missed out on the fact that a) slow and expensive growth of battery power densities would mean that such headsets would be impractical and b) always-on, always-connected devices give everyone the ability to argue with everyone. We don’t use our pocket supercomputers to call people — we use them to post.

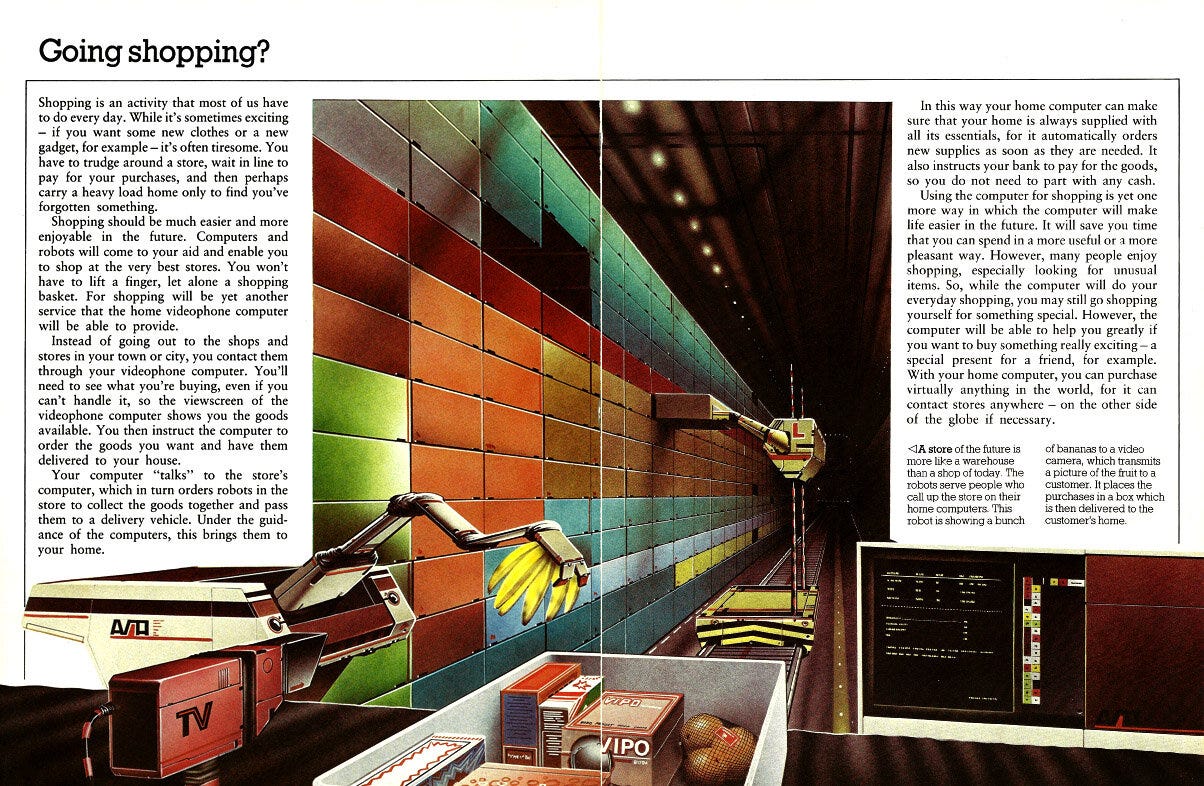

Kurzweil systematically overestimates the impact of the objectively cool technology while missing out on the “basics” like, instagram, sharing memes (formerly known as, jokes), and ordering groceries. Applications that have become a part of the bedrock of humanity. Billions are spent online every day by billions of people who talk to each other using some form of social networking. For hundreds of millions of these people, Facebook / Meta is The Internet and The Web.

Yes, a world where everyone shares pictures of their lunch with everyone else is a banal one, but it evidently matters to those doing it. They don’t care about promised “hyper-realistic” 3D worlds in which they can see the floating torsos of their friends. They care about fulfilling their hunger for social acceptance and approval; their creature comforts, no matter how small; and the warm, fuzzy afterglow of human connection (or, the rush of argument).

I’ve noticed that technologists tend to dismiss these needs as as mundane or trivial. A few understand - in an abstract sense - that people desire comfort, connection and standing, but fewer appreciate the impact this has on the world and how technology matures.

If human progress is the story of technology alleviating wants, technological progress is the story of humans amplifying desire. To fulfil core needs in ever more expanding ways. Steve Jobs understood this and shaped Apple around it;

Jobs: Who do you think will be the main beneficiary of the web? Who wins the most?

Reporter: People who have something... Jobs interjects To sell!

Reporter: To share. Jobs: To sell!

Reporter: You mean publishing?

Jobs: It's more than publishing. It's commerce. People are going to stop going to a lot of stores. And they're going to buy stuff over the web!

— Wolf, Gary. "Steve Jobs: The next insanely great thing." Wired, February 1996. Accessible here.

the internet. derivative or profound?

Almost all of the many predictions now being made about 1996 hinge on the Internet's continuing exponential growth. But I predict the Internet, which only just recently got this section here in Info.World, will soon go spectacularly supernova and in 1996 catastrophically collapse.

[…]

So, in 1996, CD-ROMs through Federal Express will emerge as the information

superhighway. Instead of an Internet brimming with Web pages under construction, too few of us will haunt ghost pages.I hope I'm not being too negative. Tell me if you think so.

— Metcalfe, Robert. “From the Ether: Predicting the Internet’s catastrophic collapse and ghost sites galore in 1996.” InfoWorld, 4 Dec 1995. Accessible here.

If you have a certain kind of mind, it’s likely that you’ll love watching videos of Clifford Stoll. I am a superfan. It’s one of the smaller fandoms in the world, but his Klein bottle warehouse (and its tiny robot forklift), writing, and videos on mathematics have been a source of deep joy over the years. I have simple tastes. Give me a video of Dr. Stoll talking about how math isn’t about numbers, and I’m a happy woman.

But he’s not famous for his explorations of topology. Not to most people. Amongst certain people, he’s known for a work-related incident that occurred while he was at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL).

Dr. Stoll’s supervisor approached him about an accounting discrepancy. It was a tiny amount, just a few cents, but Dr. Stoll became so taken with the problem that he spent ten months of his life tracking down every single avenue related to this tiny accounting error. Sometime during these ten months, his project went from being about a heroic physicist plumbing the depths of accounting minutiae to a bonafide spy thriller. He had uncovered a scheme by a German engineer, Markus Hess, to infiltrate US defense networks to steal “sensitive semiconductor, satellite, space, and aircraft technologies” on behalf of the Soviet Union.

The year was 1986, and he had discovered the first state-sponsored data breach on the public record. The subject of Dr. Stoll’s first book, “The Cuckoo's Egg: Tracking a Spy Through the Maze of Computer Espionage.”

But there’s another reason why Dr. Stoll’s famous. Or infamous.

In 1995, 9 years after the espionage incident, Dr. Stoll published a widely-shared article in Newsweek called “The Internet? Bah!” about a technology that would never take off; the Internet. It was the subject of his second book, “Silicon Snake Oil — Second thoughts on the information highway.”

It’s worth quoting the article’s start verbatim,

After two decades online, I’m perplexed. It’s not that I haven’t had a gas of a good time on the Internet. I’ve met great people and even caught a hacker or two. But today, I’m uneasy about this most trendy and oversold community. Visionaries see a future of telecommuting workers, interactive libraries and multimedia classrooms. They speak of electronic town meetings and virtual communities. Commerce and business will shift from offices and malls to networks and modems. And the freedom of digital networks will make government more democratic. Baloney.

Do our computer pundits lack all common sense? The truth in [sic] no online database will replace your daily newspaper, no CD-ROM can take the place of a competent teacher and no computer network will change the way government works.

Consider today’s online world. The Usenet, a worldwide bulletin board, allows anyone to post messages across the nation. Your word gets out, leapfrogging editors and publishers. Every voice can be heard cheaply and instantly. The result? Every voice is heard. The cacophany more closely resembles citizens band radio, complete with handles, harrasment, and anonymous threats. When most everyone shouts, few listen. How about electronic publishing? Try reading a book on disc. At best, it’s an unpleasant chore: the myopic glow of a clunky computer replaces the friendly pages of a book. And you can’t tote that laptop to the beach. Yet Nicholas Negroponte, director of the MIT Media Lab, predicts that we’ll soon buy books and newspapers straight over the Intenet. Uh, sure.

— Stoll, Clifford. ‘The Internet? Bah! Hype alert: Why cyberspace isn’t, and will never be, nirvana’. Newsweek, 27 Feb 1995. Accessible here.

It’s tempting to chalk up this article as yet another incident of “experts getting it wrong.” But that’s neither an interesting nor a productive response. It’s worth taking a moment to ask why Dr. Stoll got it wrong.

Out of all the people on Earth in 1995, you would have expected one of the early sysadmins, someone who had been online since (at least) 1975, to be amongst the people to get it right. He had been living in the future for two decades at that point. How could someone so brilliant and steeped in the tech be so wrong?

refining the hypothesis, OCPs v. ICPs

An Outside Context Problem was the sort of thing most civilizations encountered just once, and which they tended to encounter rather in the same way a sentence encountered a full stop.

The usual example given to illustrate an Outside Context Problem was imagining you were a tribe on a largish, fertile island; you’d tamed the land, invented the wheel or writing or whatever, the neighbors were cooperative or enslaved but at any rate peaceful and you were busy raising temples to yourself with all the excess productive capacity you had, you were in a position of near-absolute power and control which your hallowed ancestors could hardly have dreamed of and the whole situation was just running along nicely like a canoe on wet grass... when suddenly this bristling lump of iron appears sailless and trailing steam in the bay and these guys carrying long funny-looking sticks come ashore and announce you’ve just been discovered, you’re all subjects of the Emperor now, he’s keen on presents called tax and these bright-eyed holy men would like a word with your priests.

— Banks, Iain M. ‘Excession’. 1996.

For most people encountering this wild new thing called the Internet in 1995, it was (or was going to be) an Outside Context Problem, or OCP.

Almost no one at the Yellow Pages publishers, most retailers, book stores, fax machine manufacturers, small newspapers, independent book publishers, and record labels had encountered anything like the web of that era. Neither had their customers. For them, its potential, as well as its impact, was the full stop at the end of their sentence. They just hadn’t realized it yet.

Conversely, for Dr. Stoll, the Internet and the Web were something firmly within his domain and context — an Inside Context Problem, or ICP. He had spent two decades tinkering with it. His friends had gamed on it.1 They’d chatted on it.2 They’d bought things from one another on it.3

His familiarity had bred contempt.

Everything promised during the Dot Com hype of the ‘90s were things he and his friends had already created or played with at some point in their careers. He had already gone through the hype and the inevitable disillusionment. From his perspective, everyone hawking an iterative improvement on decades-old technology was pulling a fast one over people who didn’t know better. It certainly didn’t help that many of the Dot Com boom companies of the time were outright scams.

If you read the rest of his piece, you’ll find that we’ve caught up with his cynicism, albeit from a very different place, with trillions of dollars in monetary value being created along the way,

What's missing from this electronic wonderland? Human contact. Discount the fawning techno-burble about virtual communities. Computers and networks isolate us from one another. A network chat line is a limp substitute for meeting friends over coffee. No interactive multimedia display comes close to the excitement of a live concert. And who'd prefer cybersex to the real thing? While the Internet beckons brightly, seductively flashing an icon of knowledge-as-power, this nonplace lures us to surrender our time on earth. A poor substitute it is, this virtual reality where frustration is legion and where—in the holy names of Education and Progress —important aspects of human interactions are relentlessly devalued.

Our familiarity has bred contempt as well. The Internet, the technological miracle, has become mundane. Just like it happened to the radio, electricity, vehicles, internal combustion engines, heavier-than-air flight, space travel, submarines, supersonic flight, laser surgery, robots, precise global navigation… We are all on the miracle treadmill — forever chasing novel miracles before discarding them as mundane.4

The more a technology is used towards fulfilling core desires and needs — especially social needs; the stronger this dismissal becomes. Did any technologist take people sharing lunch over instagram seriously in 2012? Snapchat filters in 2015? Uber in 2011?

If the miracle treadmill blinds us to a technology’s possibilities during its ascent, it also causes us to overestimate immediate impact on genesis. Think Webvan v. Amazon Fresh. Vine v. TikTok. ALIWEB, JumpStation, AltaVista v. Google.

Or, on a larger scale, the ambitious post-Apollo timelines where Apollo-era scientists, engineers and leaders reasoned to n from the glow of lunar success.

It seems that the only way out is to perspective shift on self-command — to see the new as if it was old; and the old as if it was new.

Dr. Stoll had, likely, at some point, used Talkomatic, the first true messaging app in 1975,

from, Stone, M. David. “Getting Online for Education.” Ziff Davis, Inc. 1 May 1984. pp. 221. Accessible here.

The first e-commerce transaction is likely to be grad students selling marijuana to each other via the ARPA-net. There’s something oddly comforting with students using a multi-billion dollar defense technology to sell drugs. The more things change, the more they remain the same.

In 1971 or 1972, Stanford students using ARPA-net accounts at Stanford University's Artificial Intelligence Laboratory engaged in a commercial transaction with their counterparts at Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Before Amazon, before eBay, the seminal act of e-commerce was a drug deal. The students used the network to quietly arrange the sale of an undetermined amount of marijuana.

— Markoff, John. ‘What the Dormouse Said: How the Sixties Counterculture Shaped the Personal Computer Industry’. 2005.

I grew up with the web. If you’d told me when I was 12 that we’d smash through Turing’s wildest dreams before I turned 30 with giant neural networks that cost billions to train and display emergent behavior and properties… I’d have thought you were pulling my leg. And yet, we live in a world with sci-fi level AI that is routinely dismissed as “useless,” with a large segment of the population joining in on the derision. Crazy.

good wakeup call, indeed!